Thoughts on satire, pop culture and the Gospel

I don’t usually use column space to respond to letters I get either in support of, or in opposition to, a piece I’ve written. However, the response I’ve received about my column last week on “The Golden Compass” has prompted me to add some more points to ponder.

To get everyone up to speed, “The Golden Compass” is a movie due out this holiday season that is at the heart of much controversy. The author of the “His Dark Materials” trilogy, the inspiration for this movie, is a noted atheist who many claim is determined to destroy children’s faith through the propaganda in his books.

Last week, I drafted a satirical piece that poked fun at those who have such profound issues with this movie and the preceding books, yet who have not seen either, short of a commercial on television and some e-mail rumor that’s been spreading like wildfire across the Internet. In fact, there was an article in the paper to this effect a little more than a week ago.

While most people appreciated the humor of the piece, there actually were those who didn’t get somehow that it was satire. I got all kinds of angry e-mails calling me a hypocrite, accusing me of propagating a narrow-minded position that did more harm than good.

To those who haven’t read my columns at all over the past two years and just happened to pick this one up with no background, I can understand this misunderstanding. For anyone who has read my columns before, come on, you know me better than that.

There were more than a few responses from the “other side,” criticizing my attacks on people with more conservative ideology. One reader actually compared my satire to the Nazi propaganda cartoons published against Jews prior to World War II.

Ouch.

A word of caution about this sort of “slippery slope” argument: First, consider that the cartoons in Germany were not about a set of beliefs people of all backgrounds maintained, but rather castigation of an entire race of people for who they were by birth. While someone cannot be criticized for who they were born as, they certainly should be prepared to undergo some scrutiny for what they claim to believe, including me.

Also, it should be noted that much, if not all, of the anti-Semitic propaganda in Nazi Germany was state-sanctioned, which inherently means a manipulation of free speech. While some folks may object to my point of view, it’s not propaganda, because I’m free to write what I want. There’s a big difference, and one that is the cornerstone of our democracy, I think.

The point is for people on both sides of the argument to stop and think about what they believe, rather than reacting from the gut. No secular book or movie should dictate our beliefs, be it “The Da Vinci Code,” “Passion of the Christ,” “The Golden Compass,” “Harry Potter” or Kirk Cameron. Jesus challenged us to look beyond the written law even in Scripture, pushing us to find truth within ourselves. It’s easier to find it in a book or on TV, but that’s not Gospel.

I respect those with differing views and their right to air an opposing perspective, but for crying out loud, if you’re going to stand against something, know what it is that you’re condemning first. I can’t say whether or not “The Golden Compass” and the books on which it is based are good, bad, dangerous or a wonderful opportunity for rigorous debate.

Why not? Because I haven’t read them, and the movie hasn’t been released yet. My guess is, however, that New Line Cinema is as thrilled about this sort of uproar as Dan Brown and Ron Howard were about the controversy surrounding “The Da Vinci Code.” It’s the best free press they could hope for.

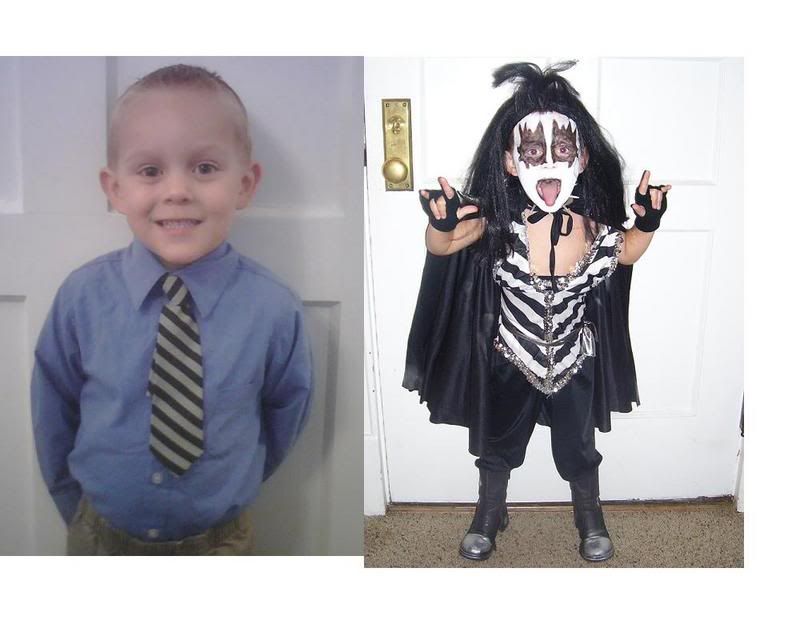

Each of us ultimately must decide for ourselves which movies and books are appropriate for us and our families. I don’t know if I’ll take my son to the movie or not; I have to know more about it first. But if I can read Nietzsche, who famously claimed “God is Dead,” all the way through college and still have faith, I’m pretty sure it will take more than a two-hour movie about a kids’ book to convince me to claim atheism.

Christian Piatt is the author of “MySpace to Sacred Space” and “Lost: A Search for Meaning.” He can be reached through his website, www.christianpiatt.com.